For the latest in Mario Matassa’s series on the secrets of Italian food, we turn to the subject of cheese, focusing on fontina, ricotta, parmesan, pecorino and mascarpone

Photos by Mario Matassa

According to my doctor, it’s okay for me to eat a little cheese every day – just as long as I always wash it down with red wine. He also recommends parmesan for weaning infants because it’s so easily digestible and such a rich source of calcium. Teething infants soothe their gums on chunks of parmesan, and their grandmothers sing to them as they feed them homemade broth with grated parmesan.

According to my doctor, it’s okay for me to eat a little cheese every day – just as long as I always wash it down with red wine. He also recommends parmesan for weaning infants because it’s so easily digestible and such a rich source of calcium. Teething infants soothe their gums on chunks of parmesan, and their grandmothers sing to them as they feed them homemade broth with grated parmesan.

The national love affair with cheese knows no bounds – it’s one of the few things Italians cannot do without. I guess that’s why astronauts Maurizio Cheli and Umberto Guidoni felt compelled to smuggle a few wedges of Parmigiano Reggiano aboard the Space Shuttle. It was subsequently discovered that this is one of the few products that remains intact at zero gravity. It has since become authorised as the only non-processed food in the diet of the International Space Station.

Word of mouth

Word of mouth

Many years ago, nearly every town in Italy had its own latteria where fresh cheese would be sold daily, in the same way as bread. It never came with any wrapping, and seldom even had a name. Nostrano (local), fresco (fresh) or stagionato (aged) were the only appellations likely to be applied. Sadly, these shops have all but disappeared and today you often have to venture a little further afield for something special. Nowadays, when I need a piece of parmesan, I drive down the road to the province of Parma. When I fancy a piece of goat’s cheese, I’ll take to a mountain track; word of mouth guides me to the source.

Whatever you are looking for, you can find it. Artisan producers still abound in Italy, though few advertise. Their shop tends to be their front living room, which invariably always smells of cheese. Stop at any bar in the province and ask for recommendations. Or, alternatively, just follow the animals. Chances are, if you see a herd of goats or sheep, someone nearby is going to be producing cheese.

A few years ago a young couple from Puglia opened a cheese shop just a ten-minute walk from my home. For us it was just like winning the lottery. The shop stocks 250-300g balls of fresh buffalo mozzarella – something you rarely see outside the southern regions, and something to which I am quite partial. I ate insalata caprese for three nights in a row the week they opened.

Geography is key

Geography is key

Like everything food-related in Italy, geography is the key to culinary happiness. Every year, die-hard cheese aficionados make the pilgrimage to Cuneo in Piedmont or Bergamo in Lombardy, the de facto cheese capitals of Italy. There, the challenge is to eat your way through the menu of cheese in just a few days. It’s a serious challenge and only the truly devoted will succeed. Piedmont and Lombardy produce no fewer than 122 and 107 (respectively) varieties of (mostly) cow’s milk cheese. So you can see why anyone who makes it to the finish line deserves respect.

But whichever region you travel to in Italy, you can rest assured that they will make their own unique variety of cheese. In fact, when it comes to cheese, in Italy variety truly is the spice of life. The Italians often pity the British for the homogeneity of their cheese. With a population in the region of 60 million in the UK, how can you possibly get by with ‘only’ 132 cheeses to choose from? The Italians, roughly similar in number, have well over 800.

With so much on offer, where do you start? First, eat local; don’t necessarily go for the named brand. In my experience, locally produced cheeses tend to be both better and cheaper. Added to that, you’re doing your good deed by supporting the local farmer. Second, if you want to eat like an Italian, don’t start with a piece of cheese (unless you are sprinkling it on your pasta) finish with it. Also, don’t cook with the most expensive cheeses, it’s a waste. If you want parmesan for pasta, buy a 12- or 24-month-old cheese. If you want to eat it in chunks on its own, look for an older cheese – say 36 months. Finally, don’t chuck out your cheese just because it’s developed a little mould in the fridge. And even the most dried out remnants of old cheese can be added to soups for a little extra flavour and texture.

Read on for a guide to some favourite cheeses (and links to super recipes for cheese lovers!):

Fontina

Fontina

The last time I was in Cogne in the Val D’Aosta, I was taken to a little restaurant to sample the local fontina cheese. The restaurant was called the Bar à Fromage. It serves nothing but cheese – a lot of cheese. In fact, there are always at least 50 varieties on hand to be tasted – and you are eagerly encouraged to taste them all. I ate fontina five different ways and it soon became clear to me why this rich melting cheese is so favoured by the people of Aosta.

Fontina is the Val D’Aosta’s most famous cheese; it is produced from the milk of the red and black Valdostana breed of cow. The best versions of this cheese tend to be produced from cows that graze on the highest pastures. The finest dish I ate that day was the fonduta – a cheese sauce made with melted cheese and egg yolks – poured over puréed potatoes. Strictly speaking, the recipe I created (gnocchi with four-cheese sauce) is not actually a fonduta as it does not include eggs in the making. It’s a simpler version but no less tasty. And you still get to try four of Italy’s best known cheeses on one spoon.

Click here for Mario’s fontina recipe.

Ricotta

Ricotta

My family is from the province of Frosinone in Lazio, so I guess ricotta is in my DNA. Back in Belfast my grandmother taught me how to make it when I was young because it was difficult to find fresh ricotta in the shops at the time – and that was a travesty.

Ricotta is made using left-over whey from cheese-making. It is reheated (hence the name, re-cooked), lightly salted and drained, and is immediately ready for use. It can also be drained, salted and smoked, or just salted and dried and left to mature, which produces a hard ricotta that can then be grated and used in pasta dishes such as the classic pasta alla norma. It can be produced from sheep’s milk or from the milk of the goat, cow or buffalo, or any mixture of them.

Outside Italy, people tend to use ricotta predominantly in cooking. I go along with that if you are buying the long-lasting supermarket variety that comes in a sealed tub. With a good fresh ricotta I tend to eat it as quickly and as simply as possible – spread on crusty bread with a drizzle of honey, or as an impromptu dessert – a sprinkling of sugar, a few slices of whatever fruit happens to be at hand and, occasionally, a few drops of brandy or liqueur. This recipe uses a hard ricotta and makes for a wonderful picnic accompaniment.

You’ll find Mario’s great ricotta recipe here.

Parmesan

Parmesan

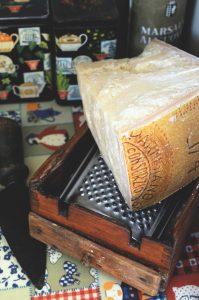

Parmigiano Reggiano hardly needs an introduction. It is, after all, the world’s best known cheese. It’s even been into outer space – what other cheese can claim that? Simply put, life in Italy wouldn’t be the same without it – or at least, pasta wouldn’t.

Parmigiano Reggiano is one (albeit the most famous) of the group of hard cheeses known generically as parmesan in the UK. It is produced only in the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna and Mantua in Lombardy. The other famous variety is Grana Padana, which can be made in Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Piedmont and Veneto. Both products have DOP status. Parmesan is used ubiquitously in recipes as a stuffing, mixed into a risotto, or sprinkled over a plate of pasta or a bowl of minestrone. The best is eaten simply in bite-sized chunks.

For Parmesan recipe inspiration click here.

Pecorino

Pecorino

Pecorino, one can say for sure, is made from sheep’s milk, because pecora is ‘sheep’ in Italian. Beyond that, generalisations are difficult. That’s because there are many varieties (over 40 at last count) and they are all different – depending on geography, the method of production, even the type of sheep!

The most famous, arguably, is pecorino romano, which despite its name is made not just in the area around Rome but also throughout Lazio, the province of Grosseto in Tuscany and in Sardinia. The latter should not be confused with pecorino sardo, also made in Sardinia. As I said, it’s a little confusing… Suffice it to say that pecorino is to the people of the south (especially Rome) what parmesan is to the people of the north: indispensable. Young pecorino is milder and is often eaten as a table cheese. Older cheeses tend to be grated over pasta. Classic dishes that demand pecorino include bucatini all’amatriciana, spaghetti alla carbonara and this one, spaghetti cacio e pepe.

Click here to find a delicious dish with pecorino.

Mascarpone

Mascarpone

Mascarpone is a cream cheese which is claimed to have originated from Lodi in Lombardy. It is most commonly bought in its long-life form (UHT) in tubs in shops and supermarkets. This cheese is used in both savoury and sweet cooking – most obviously in recipes such as tiramisù and other creamy puddings, mixed with egg yolks and sugar for a rich sauce for panettone, as a sauce used over tagliatelle and other pasta dishes or added to a risotto to lend a creamy and tangy richness.

Artisan mascarpone is made throughout the region of Lombardy and has to be eaten fresh. It can best be described as a cross between butter and cream. It is made from fresh cow’s milk which is heated, mixed with a coagulant, refrigerated for 12 hours, strained, chilled, strained again and then eaten. However (and I don’t say this very often) as a cooking ingredient the mass-produced long-life version is perfectly acceptable.