In the far southeast of Rome is a park with a long and watery history, Joe Gartman writes…

Images by Patricia Gartman

There is a place, not far from the old Via Appia, where you can step outside of Rome without leaving the city. You can almost step outside of time too, into a landscape that the old Consul Appius Claudius might have seen as he plotted his road to Brindisi. There are visitors, mostly Romans, who come to walk, or run, or let their children play, or simply to find peace; but the place is not crowded. There are no pedal cars, food truck vendors, pony rides or carousels. Most tourists don’t come, of course, because they are hurrying to see Rome’s famous sights before their time in the Eternal City runs out. But, next time, after you’ve tossed your coin in the Trevi Fountain and the monuments become a blur, you might give it a try.

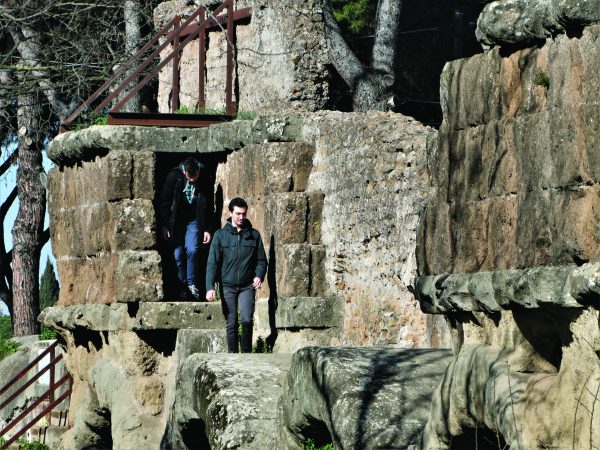

You can get there easily too. Take the Metro Line A toward Anagnina and get off at the Subaugusta. Walk four blocks southwest on Viale Tito Labieno, turn left on Via Lemonia, and when you see a low flight of stone steps on your right, take them to enter a stand of graceful umbrella pines. Ahead you’ll see a long, low structure, part ancient stone and part concrete-covered conduit. It is a stretch of the Acqua Felice aqueduct, from the 16th century, riding piggy-back on the half-buried arches of Aqua Marcia, from seventeen hundred years before. Look for a metal stile to cross it. On the other side, the noise of the city fades away.

To your right, you’ll see a grove of leafy trees, almost hiding an old stone farmhouse: the Casale Roma Vecchia, it’s called. Some time in the last two centuries it was rebuilt from a 13th-century coaching inn. Children chase each other in the shade of the house, or clamber on and about the aqueduct. Dogs snuffle in the bushes to see which of their friends have visited recently. Parents, too, like to find an arch or other perch upon which to sit or sprawl and sun themselves. Rome is full of stony fragments of its long past, so it’s not surprising that Romans treat the comparatively recent Acqua Felice like a well-worn sofa.

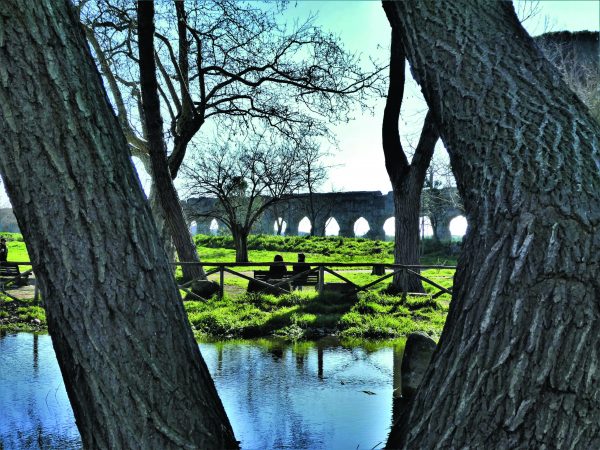

Near the old house a small pond holds schools of miniature golden carp. Beyond lies a little marsh, and birds nest among its lush trees. The marsh is called Il Piccolo Fiume Romano, and it is a wildlife refuge area. Perhaps in rainy weather there is a piccolo river somewhere in the weeds. There was a time when there were rivers here indeed; rivers made by Roman engineers. In total, seven aqueducts crossed this area; four have disappeared. Some ran underground, and have dried up; some ran in open channels, which have eroded away. Acqua Felice is still visible, of course, and a bit of Aqua Marcia. But there is one more, and it commands respect even from the blasé Romans.

South of the old house, across a wide field of grass, where picnickers enjoy lunch and lovers enjoy each other, a line of mighty arches strides across the flat landscape. The line is in giant fragments toward Rome, but it is intact for nearly two kilometres in the other direction as it curves out of sight toward its source springs, forty miles east in the Aniene Valley. This colossus is the Aqua Claudia, begun by Caligula and inherited by Claudius. It once coaxed water gently, the whole way, down a slope of exactly one Roman foot in every three hundred. In this remaining section, the structure averages more than fifty-five feet high. It was magnificent in design and execution, but ultimately the water stopped. If you come here to the Parco degli Acquedotti, the Aqueduct Park, you can walk along beside the mammoth marching arches and consider the story of Rome’s aqueducts, a story of death and rebirth…

In the 3rd century AD, Rome was served by eleven great aqueducts, delivering over a million cubic metres of water daily; Romans could use more than a dozen grand public baths, hundreds of smaller ones, and about thirteen hundred fountains, including fifteen monumental showpieces. There was irrigation for public and private gardens, and a few extremely wealthy citizens had running water in their homes. Perhaps most importantly, the constantly running water flushed sewage through the Cloaca Maxima out of Rome.

With the decline of the Western Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, the great aqueducts gradually fell into disrepair. Even before the Goths cut most of the still-functioning aqueducts in 537 AD, the water supply had decreased so severely that there were fewer than one hundred working fountains. The elevated portions of the aqueducts still marched in graceful arches across the landscape, but weeds grew in their channels. Abundant water and cascading fountains would not return for nearly a thousand years.

In the Renaissance, a series of Popes began to reclaim and repair a few of the old aqueducts, and to construct new ones, often naming the waterworks after themselves: Acqua Paola, for example, built by Pope Paul V, or Acqua Felice, named for its sponsor, Pope Sixtus V, whose birth name was Felice Peretti. In time, the purity and abundance of Rome’s water became once again the envy of the world, and a splendid variety of fountains graced the city. Once more, there were monumental fountains whose waters thundered like miniature Niagaras, poured from the recesses of triumphal arches, or were blown upward, like geysers, from the lips of sea-gods.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Joe Gartman writes about travel, history and culture, and divides his time between the southwest US and Europe. Learn more at www.joegartman.com