Adrian Mourby takes a road trip along the awe-inspiring Amalfi Coast from Sorrento to Salerno…

Images by Kate Tadman-Mourby unless otherwise stated

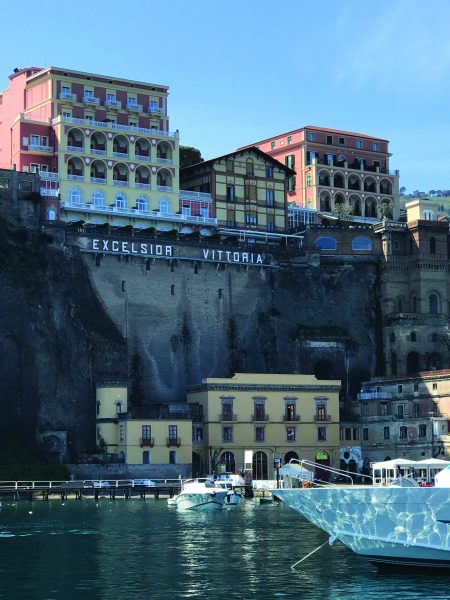

There was a seagull on our balcony, a very large one, enjoying what was left of the pre-prandial grissini. The Excelsior Vittoria in Sorrento 1 stands on top of a cliff outside the old city gates, rising up like part of the cliff-face. On our balcony Enrico Caruso spent many happy days towards the end of his life, according to a recently installed hotel plaque. He died soon after leaving Sorrento in 1921, on his way to Rome for an operation that might have saved his life. This suite has been kept decorated in an old-fashioned style, with big drapes and a marble fireplace, in his memory. My wife Kate shooed away the seagull, who left calmly, stepping out into the sky and floating away on a thermal.

Still, the bird’s departure had given us a reason to look again at Caruso’s view. Across the Bay of Naples rose Vesuvius and below us the ferry to Capri was just heading into the sunset. Tonight we were having dinner in Bosquet, the hotel’s Michelin-starred dining room, and then heading out at 3am for the Solemn Procession which takes place every Holy Thursday around the historical centre of Sorrento. The procession is organised by the Archconfraternity of Santa Monica, and it turned out to be much more dramatic than we had expected.

HOODED FIGURES

It was cold and dark as we stepped out of the hotel’s garden to encounter the procession making its way through Piazza Torquato Tasso. White-robed, hooded figures, some with flambeaux, some carrying crosses and even scourges, were singing dolefully as they passed by. At the back of the procession, Our Lady of Sorrows, a life-size statue of the Virgin Mary, was borne aloft on a silver plinth decked with white flowers. Behind her marched young boys – unhooded – with trays of white flowers. Also known as the Visit to the Sepulchres, this procession commemorates the Virgin Mary seeking her missing son. On the evening of Good Friday a similar procession, but with blackrobed figures, organised by the Confraternity of Death, enacts the Procession of the Crucified Christ.

We were fortunate to be in Sorrento at Eastertime. Our holiday plans were to drive from Naples to Salerno via Sorrento, taking in as much of the coastline as possible. We hadn’t expected a crash course in Roman Catholicism. There are few events in Campania as dramatic as those two Easter days on the Sorrentine Peninsula.

The next day we took the hotel’s lift down to the small port below and had coffee at Ristorante Ruccio. The café displays photos of Sophia Loren in the film Scandal in Sorrento (1955). Ruccio’s was one of the locations in this comedy about a retired marshal (played by director Vittorio de Sica) who returns to Sorrento and gets involved with Loren, who plays Donna Sophie, a smargiassa. That’s an Italian word I did not know. It means a show-off, the proprietor told us.

From Porto di Sorrento you can see that the Excelsior Vittoria is two separate Victorian hotels linked by, of all things, an oversized Swiss chalet. When I met up with the hotel owner, Guido Fiorentino, he told me that his family built the hotel in 1834 but extended it when Maria Sophie, the last Queen Consort of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, was coming to stay. The extension was built in the style of a chalet, which was fashionable across Europe in the second half of the 19th century. According to Cosima Wagner’s diaries, Richard Wagner completed part of Parsifal while staying in the chalet.

We spent the day shopping for tablecloths and ceramic bowls along Via San Cesareo and walking round the clifftop villas of Sorrento before descending through a 4th-century BC Greek gate to the marina. Here a trendy new alfresco restaurant called Fish & Soul served us excellent seafood in brilliant sunshine. On the way back we encountered Hotel Tasso, which has a plaque to commemorate the poet Torquato Tasso, who was born in Sorrento. There’s a second to ‘Enrico’ Ibsen, the Norwegian playwright who stayed here in 1881: “Here in the sun, Enrico Ibsen, weeping over the dark destinies of man, wrote Ghosts.”

VERTIGINOUS CLIFFS

Saturday morning we drove the 32 kilometres to Amalfi 2 via the coast road that clings to the side of vertiginous cliffs, winding through the towns of Positano and Praiano. Kate leaned out of the passenger window with her camera while cautioning me not to look at the views she was snapping. As if the road weren’t narrow enough, locals stopped their cars on bends to chat to each other. Coaches also made driving interesting, pulling over so passengers could swarm into ceramic factories built into cliffs or visit laybys selling limoncello and Amalfi’s giant lemons, the size of a rugby ball. This coastline is covered with terraces of fruit trees. The terraces seem to reach up to the sky.

At Hotel Santa Caterina, outside Amalfi, it felt warm enough for an Easter swim. Just as at Excelsior Vittoria, there was a long lift down to the shore where a small concrete jetty existed for bathers. Santa Caterina, like the Vittoria, is still owned by the same family who built it. In this case it’s the Gambardellas, who opened for business in 1906. Stepping inside is like coming into someone’s home, with paintings, objects d’art and bits of furniture that resemble family heirlooms rather than the work of one designer.

We ate that evening down in Amalfi, on the seashore at a modern seafood restaurant called Grand Marina. Afterwards we wandered round the moonlit town, which is built into a cleft in the sea cliffs and has a most dramatic cathedral. The church sits atop a long, dramatic flight of steps and has a garish façade that nevertheless successfully combines Norman, Arab and Byzantine elements. Beneath the steps is a crypt containing the remains of St Andrew the Apostle, brought here in 1208 after crusaders had diverted from the Holy Land to sack Constantinople.

We ate that evening down in Amalfi, on the seashore at a modern seafood restaurant called Grand Marina. Afterwards we wandered round the moonlit town, which is built into a cleft in the sea cliffs and has a most dramatic cathedral. The church sits atop a long, dramatic flight of steps and has a garish façade that nevertheless successfully combines Norman, Arab and Byzantine elements. Beneath the steps is a crypt containing the remains of St Andrew the Apostle, brought here in 1208 after crusaders had diverted from the Holy Land to sack Constantinople.

We were back again the next morning for a packed Easter Sunday Mass with a lot of incense and Archbishop Soricelli liberally dousing the congregation with holy water. Our holiday was taking a distinctly religious turn. After the service the shops and cafés were open, so we walked up Via Lorenzo D’Amalfi, past all the limoncello and ceramic stores as far as the ‘Donkey Head’ fountain.

Fontana De Cap ‘e Ciuccio was constructed in the 18th century for the refreshment of Amalfi’s hardworking donkeys, who linked the port with the steep streets of the town, but since 1974 it has been decorated by a complex nativity scene with shepherds and other rustic figures attached to two mountains that rise up out of the water. The donkey has been adopted as the symbol of Amalfi. We saw one shop selling plates with the rather Old Testament motto “You Shall Have No Other Donkey Before Me”.

METAMORPHOSIS

Leaving Amalfi, we drove four kilometres along the coast as far as Minori. En route we passed through the town of Atrani 3 – made famous by M C Escher in his Metamorphosis etchings – a road up to the left led to Torre dello Ziro, a ruined, turreted fortress on Monte Aureo. This was once the home of Giovanna d’Aragona, the widowed Duchess of Amalfi who scandalised her family in 1498 by marrying her butler. The duchess’s brothers killed them both. The story is loosely retold by John Webster, a near contemporary of William Shakespeare, in his play The Tragedy of the Duchess of Malfi.

Minori 4 is a small seaside town with an 18th-century basilica that contains the body of Saint Trofimena, which was discovered here on the beach in the 7th century. According to local legend, the Sicilian saint was killed by her father for refusing to marry a pagan. He squashed her into an urn and threw it into the sea. Her corpse eventually washed up at Minori.

After looking at the remains of the town’s Roman villa with its Pompeiian frescoes, we drove back two kilometres to spend the night at Villa Scarpariello, a boutique hotel within the Valle delle Ferriere nature reserve. This began life as a 16th-century watch tower on this frequently raided coast but is now a very colourful hideaway. Past guests have included King Umberto II, Jacqueline Kennedy and Greta Garbo. Garbo vacationed here in 1938 with the conductor Leopold Stokowski during an affair that took them eventually to Capri.

UNBROKEN BEACH

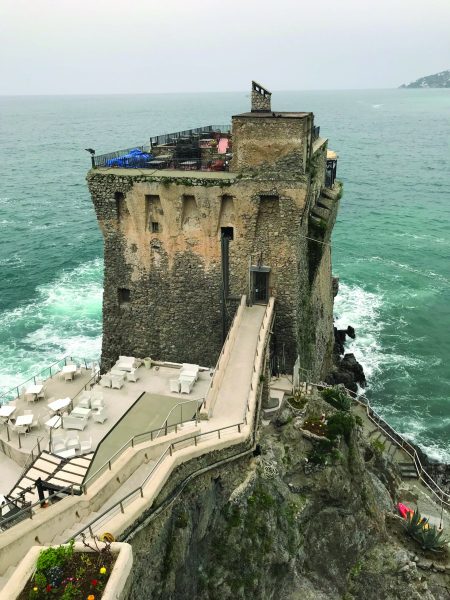

The next morning we zoomed past Minori to visit neighbouring Maiori 5 , another seaside town, this time with the longest unbroken stretch of beach, at 930 metres; it is also one of the few sandy beaches along the Amalfi coastline. The Romans took Maiori from the Etruscans in the 3rd century BC. Around 1000 AD the town became part of the Norman Principality of Salerno – and it still has a very impressive Norman watch tower jutting out into the sea, and a 13th-century church, Santa Maria a Mare, which is topped with alternating bands of dazzling yellow and green maiolica tiles.

The beach and town of Maiori featured in four of Roberto Rossellini films. Today you can still recognise street corners that were used in Rossellini’s masterpiece Viaggio in Italia (1953), which starred George Sanders and Ingrid Bergman. These days a film festival is held every November in Maiori that commemorates the director with its Premio Internazionale Roberto Rossellini award.

Approaching Salerno we stopped off at Vietri Sul Mare 6 . This town is known for its polychrome ceramics and for the remarkable “Palazzo” Solimene, which was built in 1954 by the architect Paolo Soleri. Solieri’s client was the talented local ceramicist Vincenzo Solimene (1925-2007), who wanted a factory. What Solieri presented him with was a rippling design covered in green and terracotta vases that recalls Gaudí’s extravagant work in Barcelona. Today Palazzo Solimene still produces ceramics – crockery and floor and wall tiles, all worked and painted by hand.

From here we drove down into Salerno 7 which seemed huge after all these tiny seaside towns. Salerno is a major Italian port but also has a medieval core and a grand late- 19th-century promenade known as Lungomare Trieste. As this was Easter Monday, we parked as close as we could to the cathedral, passing rows of Renaissance palazzi, many of them built by merchants who made their wealth trading in the city.

The cathedral was begun in 1076, after Norman soldiers under Robert Guiscard seized the city from the Byzantine Empire. It has a remarkable bell tower, that once again fuses Arab and Norman styles, and a massive marble pulpit known as Ambone D’Ajello in a raised-room style more often found in Eastern Orthodox churches. The cathedral’s big metal doors were seized on a raid in Constantinople in 1099. But the cathedral is best known for containing the body of St Matthew, who is said to have died in Ethiopia. Three hundred years after his death, Matthew’s remains were transported by merchants to the westernmost part of Brittany, from where a local Roman commander brought then to Campania. A long story of burial and reburial – and even loss of the bones at one point – ended in 1081 when a monk brought them to Roger Guiscard, who was now calling himself Prince of Salerno. Guiscard reburied these remains in the crypt of his new cathedral. Today Matthew the Apostle is the patron saint of Salerno and a silver statue of him is carried around the city centre every year on 21 September.

The cathedral was begun in 1076, after Norman soldiers under Robert Guiscard seized the city from the Byzantine Empire. It has a remarkable bell tower, that once again fuses Arab and Norman styles, and a massive marble pulpit known as Ambone D’Ajello in a raised-room style more often found in Eastern Orthodox churches. The cathedral’s big metal doors were seized on a raid in Constantinople in 1099. But the cathedral is best known for containing the body of St Matthew, who is said to have died in Ethiopia. Three hundred years after his death, Matthew’s remains were transported by merchants to the westernmost part of Brittany, from where a local Roman commander brought then to Campania. A long story of burial and reburial – and even loss of the bones at one point – ended in 1081 when a monk brought them to Roger Guiscard, who was now calling himself Prince of Salerno. Guiscard reburied these remains in the crypt of his new cathedral. Today Matthew the Apostle is the patron saint of Salerno and a silver statue of him is carried around the city centre every year on 21 September.

We had seen a lot of saints and churches on this trip so it was time to walk along Lungomare and get some fresh air before driving back to Naples airport. Although it had taken us four days to drive from Sorrento to Salerno, the trip back to Naples, bypassing the Sorrentine peninsula, took us under an hour.

Enjoyed this article on the Amalfi Coast? Read more about this beautiful area in our archive.