We talk a lot about what a painting is of, and what it means, but not so much about what is made of, and how it was painted.

Often when we are talking about paintings, the materials used to actually make the painting rarely get a mention. However, just like the ingredients of a great pizza or melt-in-your mouth cannoli, the materials are very important for the painting’s longevity and brilliance. The painter, like the chef, needs great ingredients from the beginning in order to properly produce his masterpiece and bring forth his talent.

In the Medieval and early Renaissance period, paintings had a wooden support. Seasoned poplar wood was most commonly used in Italy; sometimes also willow or linden wood. Most of the wood panel supports were constructed by fastening together numerous panels, which were then sanded and planed. The wooden support was then coated with ‘size’, which is a mixture of gelatin or glue made from animal skins. Often there would have been a piece of linen cloth laid on the surface, which created a greater adhesive surface for these liquid preparatory films. On top of this, up to

15 layers of gesso (chalk mixed with glue) were added; the final layer had to be as smooth as ivory. This white ground was what the painters used as the base surface for the colour medium, which was first the tempera paint medium and then, by the late 15th century, also oil paint.

Egg tempera painting

Egg tempera painting was the technique used in the Medieval period. The word tempera originates from the Latin word temperare, meaning ‘to mix’. The colour pigment is mixed with an emulsion, with egg yolk as the principal ingredient (sometimes the whole egg was used). The colour was mixed, or ‘tempered’, with the egg.

The tempera medium dries rapidly and it cannot be applied too thickly, so it never achieved the saturation of colour that would be possible with the oil medium in later years. However, tempera paintings are long lasting and their colours don’t deteriorate over time as much as those mixed with oil. In the Medieval period, when painting was symbolic and not realistic, the thick opaque effect from the tempera paint was ideal. The blue of the Madonna’s mantle in the large and imposing Maestà-type paintings of the Medieval period depicting the Virgin Mary on her throne as Queen of Heaven was a solid mass of colour, strong and dense. This technique works well for these paintings, which are to be seen from afar in dark, large churches.

Medieval painting characteristically has a gold background (a symbol of heaven) with painted images of the Holy Family and saints, and so the tempera medium worked well in making the distinct colours of the saints’ clothes compete with the intense background. Narrative and volume took a back seat in the Medieval period to conveying the greatness of Heaven and the eternal presence of the holy characters. Domestic painting was in the form of devotional images too, but was only for the very wealthy and so quite rare. Most painting was made for a religious space and was on a large scale. Tempera painting was well suited to this environment.

With the advent of Humanism and the Renaissance in Italy the painting market changed significantly. The rise of a new class of wealthy merchants increased the pool of artistic patrons and there developed a new desire to decorate the domestic environment, not just the civic and religious domains. The demand to show the natural world in all its complexity and detail reflected the renewed value given to the natural world.

The development of mathematical perspective is directly linked to this new valued perspective given to the everyday on Earth, as had once been the case in Antiquity. Painters were now required to understand mathematics for the rendering of space on the flat surface and had to concentrate on depicting details of the flora, fauna, physiognomy and architecture. Tempera was superseded by oil painting because it provided many more possibilities in satisfying the new needs for pictorial depiction.

Oil painting

There were three main ingredients in oil painting: colour; the binder, which in this case is oil (usually linseed oil was used); and the thinner, turpentine, which made the paint easier to apply with a brush. The oil medium enabled painters to spend longer on the painting’s execution and to achieve greater shades of the same colour through the glazing or layering of the colour applied.

Furthermore, oil painting gave painters the opportunity to

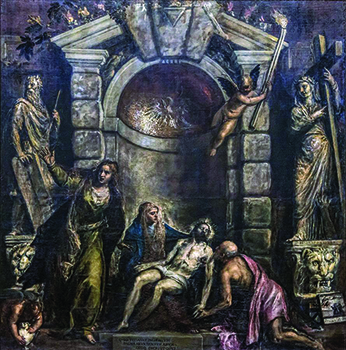

use long brush-strokes, something not possible in tempera painting, and this changed painting entirely, providing an unprecedented freedom of expression. Colour, more than ever before, became the true protagonist. Titian (1488?-1576) was the undisputed master of oil painting in the 1500s. He explored the possibilities of colour like no other, both in terms of the saturation of colour and tonal properties that could be explored as well as in the very material substance, playing with the build of paint, or ‘impasto’, to create depth of expression on the canvas.

Venice had the most important market for the pigments used in the Renaissance. Many of these pigments came from the East and arrived in Venice before being sold on to the European market. The first book ever written listing and describing the colours used in dying and painting was printed in Venice, which also happened to be the largest and most productive printing centre in Europe in the 1500s.

The most expensive colour was lapis lazuli blue, otherwise known as ultramarine, because the blue stone only came from Afghanistan and was rare even there. It cost more than gold. Azurite, a copper mineral, was also used for the colour blue as it was widely found in Europe. Cinnabar is a natural ore and was a popular source for a red-orange; the colour was called either cinnabar or vermilion. Malachite was a very common source for green in the Renaissance, and had been used in Antiquity. The painters made up their colours themselves in their workshops.

Wood and canvas

Canvas support supersedes wood panel more or less at the same time as tempera bows out to the oil medium. The material was stretched over a wooden frame and, like wood panel, was prepared with layers of gesso. Canvas was easier to transport – it could be rolled up – and it was much lighter, an important consideration for a city like Venice which, through necessity, had to source lighter materials due to her urban lagoon foundations. Again, it is not surprising that the Venetians specialised in the production of large canvases as they could draw on their expertise in sail manufacture for shipping.

Canvas provides a different painting effect. Due to the nature of the woven material it doesn’t have as smooth and shiny a surface as a panel painting could have. Colour is never entirely applied evenly on the weave, which produces different paint thicknesses, which changes the painterly effect. The breadth of knowledge in painting production that was transferred from maestro to student in the workshop is simply astounding. These bottegas were the most innovative places in the city. It is no wonder that we are lining up to admire them centuries later.

About the writer:

Freya Middleton is a private tour guide and writer who lives in Florence, Tuscany. You can read her blog online or learn more about her tours at www.freyasflorence.com.