They are double-sided portraits, painted by Piero della Francesca, who was the court painter at the court of Urbino

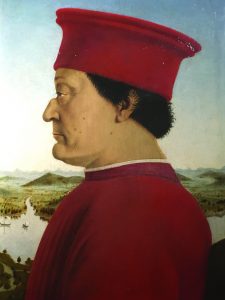

These portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino are amongst the most famous portraits in 15th century Italian art. Why? Because they are revolutionary in their depiction and fascinating in their symbolism. They are double-sided portraits, finished in the 1470s, and painted by Piero della Francesca, who was the court painter at the time for the Urbino court. Today, a 19th-century frame holds them static; however, the portraits were once hinged and could be closed. Maybe the duke, Federico of Montefeltro, had them made in this way so that they would be portable and he could take them with him when he moved around his territory.

He was devastated when Battista Sforza (depicted), his second wife and much younger than he, died shortly after the birth of their seventh child, a long-desired first son after six daughters. After her death, in 1472, he retired from his day job as an extremely successful mercenary commander, and concentrated solely on his intellectual pursuits. The duke invested much time and money in transforming his city and, above all, his palace, into a Renaissance hub of artistic production and the exchange of ideas. He completely rebuilt the ducal palace and filled it with precious artefacts and manuscripts. He had the money to do this, having received handsome remuneration over the years for offering his military talents to others: to the republics of Florence and Venice and to the Pope, to name but a few of his clients.

The duke and duchess are depicted here in the attire of nobles: he with his red surcoat and hat; she with her pearl choker headdress and damask dress. They are together, symbolically shown by the continuity of the landscape, beautifully rendered in aerial perspective, stretching out behind them.

The portraits are hung in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence

They are shown in sharp profile and similar to how the Ancient Roman emperors were depicted on their medallions and coins. Maybe the duke wanted his public to draw the connection between himself and the great Julius Caesar with his successful campaigns and great strategy. Normally the heads of antiquity were shown looking to the right; however the duke opted for a little poetic licence in representation and opted to show his best side, rather than being too much of a stickler for tradition, and he is represented looking to the left. The vain decision is understandable when you know that he had lost his right eye in a joust, which also damaged the bridge of his nose. Furthermore, facing in this direction means that he looks to his lost love.

These are some of the first portraits since antiquity freed from a religious environment. This reflects a big change in society. All elements of the medieval world are gone here. The re-emergence of the portrait in art shows that value was once more being given to life on earth rather than exclusively to the heavenly sphere. It reflects the return of an anthropocentric society. The last time that portraits had been commonplace was in ancient Rome.

Portraits of patrons who commissioned paintings began to appear in the religious painting in the mid-1300s and had become much more frequent by the 1430s. Initially they were represented as tiny to show the difference in status with the religious protagonists; in the first half of the 15th century they were depicted of equal size. Here we see the duke and duchess freed from any religious scene and they themselves are the protagonists. The selfie is back!

These portraits don’t herald in a moment of rejection of the heavenly sphere but a shift in the relationship between how man viewed life on Earth and what he does during this lifetime. The here and now was given the prime importance it had held in Antiquity, and the concept that man is the measure of all things returned.

All man’s deeds, both in virtuous and spiritual devotion and in the extent of his earthly courage and secular excellence would help one’s plight to heaven. So these portraits shouldn’t be viewed in a purely superficial sense of two people wanting to record their physical presence but within a much deeper philosophical context.

The portraits are ingeniously double-sided. When the diptych were closed there was still the duke and duchess’s portraits on the exterior. They both appear in miniature and are seated on triumphal chariots. The duchess is being pulled by unicorns, a symbol of chastity, and accompanied by the three theological virtues: faith, hope, charity; and modesty. The duke is being crowned by fame and pulled by stallions, accompanied by the four cardinal virtues: temperance, justice, prudence, fortitude.

She has all the mystical and spiritual elements for two reasons. First, being the woman, her role is to ensure a domestic atmosphere most conducive to the saving of her family’s souls. Second, she has already died and so this is the realm where she inhabits at the time of the painting’s execution. The duke’s role is public and he must defend the dukedom and his family, and so his virtues reflect the tools he must cultivate to best carry out his duties.

These earthly and heavenly virtues together form unity and they are the instruments required for achieving excellence. The Renaissance welcomed once more this concept of the importance of equilibrium between matter (body) and soul, which when in sync make it possible for humankind to get that much closer to perfection and perfect harmony. This is the ultimate significance of this painting’s use of the portraits as a vehicle. They express perfect balance, with equal attention given to male and female, body and soul, earthly domain and spiritual realm – even the balance between word and image, because the Latin epigraph extols the greatness of the duke in the same number of words and lines as the epigraph for the duchess waxing lyrical about her extreme virtue.

This selfie of the Renaissance remains resolutely heavenly in spirit and provides so much food for thought for us here on Earth, even in the 21st century.

FREYA MIDDLETON is a private tour guide and writer who lives in Florence, Tuscany. You can read her blog online or learn more about her tours at www.freyasflorence.com