This month, Mario Matassa continues his delicious journey through the fascinating world of Italian cuisine, tackling, in this issue the all-important first course

In a country that is as much defined by its gastronomy as it is by its history, art and architecture, there is perhaps no better place to begin to understand Italy than at the table. And it is with il primo (the first course), I would dare to venture, that Italian cuisine is primarily defined. Today, the first course dishes listed on the menu of any good Italian restaurant are recognised, appreciated and imitated the world over. They have established themselves on tables across every part of the globe, taking their rightful place in the pantheon of the world’s great cuisine. Pasta has never been more fashionable. Indeed, such is its popularity that the somewhat erroneously labelled ‘spag bol’ (strictly speaking it doesn’t exist in Italy), was voted the UK’s favourite food!

But it was not always so. As little as 25 years ago, outside its country of origin, pasta was generally viewed with indifference. Its meteoric rise to stardom can be explained on a number of levels. Pasta is relatively simple and quick to make, it is perhaps one of the most versatile staples available and it is relatively inexpensive. It is, in short, accessible and easy to live with. But more than this, the increased popularity of pasta must in some way be attributed to the association it holds in the popular imagination with its mother country.

Did you know?

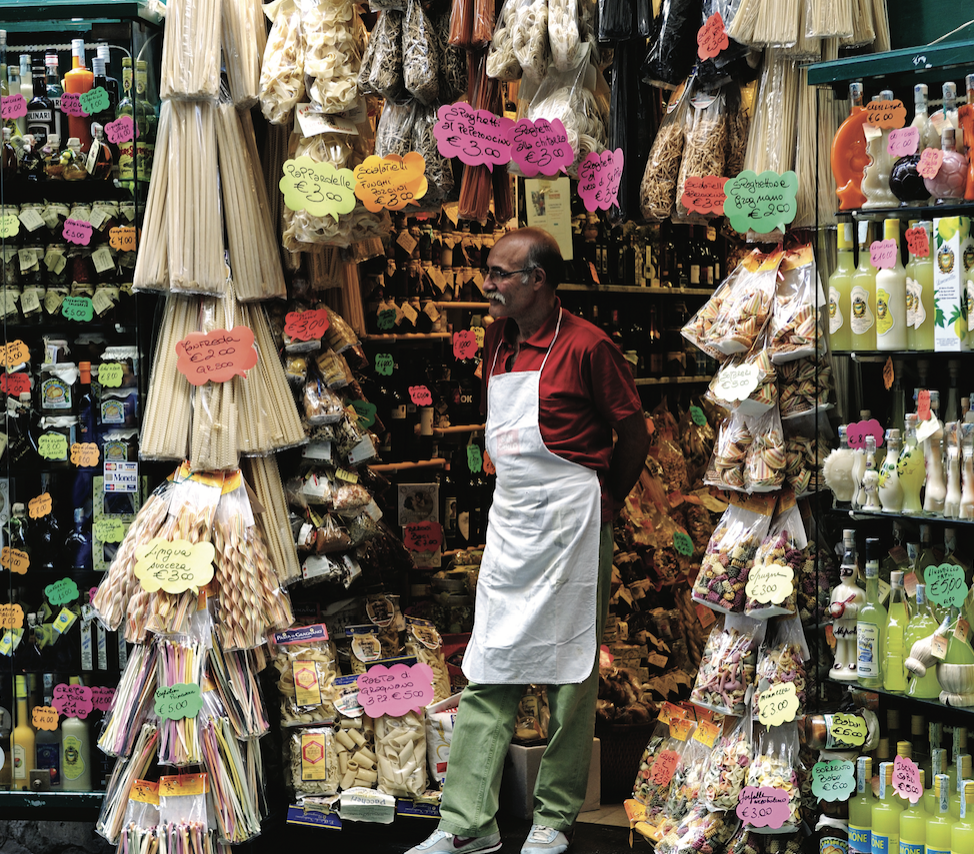

Pasta is in some ways one of the earliest forms of fast food. In 1787 Goethe, writing in his diary ‘Travel to Italy’ describes the maccheroni vendors selling pasta from their stalls in the streets of Naples, emphasising how on lean days (when the Catholic religion forbade eating meat) “thousands of people take their meals away wrapped in paper”. Now that’s what I call a takeaway!

No dish better evokes the image of Italian family and lifestyle than the ubiquitous, overflowing bowl of spaghetti covered in a fresh tomato sauce. Moreover, the mere mention of ragù alla Bolognese, pesto alla Genovese, carbonara or puttanesca sauce is enough to conjure the image of a Mediterranean idyll and send the hungry aficionado racing to the nearest restaurant, supermarket or travel agent. And it’s not just pasta! In recent years the popularity of Italy’s alternative primi – most obviously rice and minestrone – have begun to capture both taste buds and imaginations outside the peninsula.

Crazy about Pasta

Pasta! No other food better symbolises the culture of a nation and its people. It is the most ‘Italian’ of all foods – the one that is instinctively associated with Italy by people the world over.

The Italian love affair with pasta holds no bounds. Indeed, such is the importance of the national dish that one early travel writer stated categorically that “a capacity to eat and enjoy pasta is an essential requirement for an Italian tour”. Who could ever imagine visiting the peninsula without at least once (daily) sampling the local pasta? As for Italians, well a day without pasta is… actually I’m not sure what it is, as I’ve never tried it. And I’d be hard pushed to find an Italian that had.

So it should hardly come as a surprise to learn that Italians consume more pasta than any other nation in the world. Estimates by the International Pasta Organization put the figure at approximately 28kg of pasta per person per year. To put that into perspective, the average person in the UK is estimated to consume a mere 2.5kgs. It’s probably therefore no coincidence then that the figure of 28kg per year breaks down into approximately 80g of pasta per person (the standard serving) per day, 365 days of the year. So, joking aside, the figures do suggest that the average Italian does eat at least one bowl of pasta every day of the year!

To the uninitiated, the idea that someone eats pasta day-in, day-out, every day of the year may seem somewhat monotonous. Some might well ask: does this make Italy a culinary bore? On the contrary, actually, because such is the depth and variety of the national dish that you could, in fact, comfortably enjoy your daily ration for a whole year (and then some) and never once have to face the same dish twice. In fact, New York City restaurateur Tony May once said: “There’s no reason why you should eat the same type of pasta with the same sauce more than once in your whole lifetime”. And that’s no exaggeration! A world directory of pasta listed 142 different types… that is, 142 that begin with the letter ‘C’! And just to stretch the point a little further, the directory categorised pasta around name, shape and type. If one were to expand the listing to include sauces and methods of cooking too, it would probably be endless.

Short history of Pasta

Some years back a popular misconception held that Marco Polo brought pasta to Italy from his travels to China in the 13th century. That myth has since been exposed, but it does highlight a cautionary tale. The definitive book on the history of pasta has yet to be written. As it stands, what we currently know about the origins of pasta and, in particular, its pre-modern history, is as much shrouded in mystery, myth and assumption as it is in fact.

The available evidence suggests that pasta has shared something of a parallel history, having developed in some form or other both in the Far East and in Europe well before Marco Polo ever took to sea. There is some evidence that pasta dates back to the Romans, or even earlier, to the Etruscans. The difficulty is that the different terminology used to denote pasta leaves reasonable doubt as to whether our ancient predecessors were making and eating pasta as we know it today.

The history of pasta from the middle ages is better documented. Early references suggest that pasta – even if it pre-existed in some form – arrived in Italy through Sicily via north Africa. From here, it travelled across the water and by the late 13th century, as documented in cookbooks, cooks in cities running the western coastline from Genova through to Naples down to Palermo had adopted itriyya (as it was called), turning it into vermicelli and maccheroni.

But it wasn’t until the 17th century that the pasta revolution really took hold. This time, Naples was at the epicentre of the storm. The demand from a growing (and hungry) population – it was the most populous city in Italy at the time – was met through technological advancement. The invention of the mechanised press meant that pasta, for the first time, could be produced in large quantities and at lower cost. In a few short years, pasta secca became the symbol of the city, to the extent that Neapolitans earned the nickname ‘mangiamaccheroni’ – or maccheroni eaters. In 1840 the first industrial pasta plant opened in Torre Annunziata, just south of Naples. A few years later, in 1844, the first recipe for pasta with a tomato sauce appeared in a Neapolitan cookbook. The rest is just history!

Flour and Water

That most basic combination of flour and water (sometimes egg) is a national preoccupation. If Italians are not making, eating or talking about pasta, chances are they are dreaming about it! Although I would not wish to overstate the case, pasta in Italy is a common currency of conversation.

Agnese Moruzzi is a veteran pasta maker. To say that she can make pasta with her eyes closed is hardly an exaggeration. It seems that every time I pass by the 72-year-old’s house she is making some sort of fresh pasta. In the run up to Christmas, Agnese makes on average 3,000 ravioli to see the family through the festive period. Throughout the year, with her husband, Carlo, a son, a daughter and five growing grandchildren to feed, not to mention friends and the odd passing journalist, she takes to the task at least twice a week. “Don’t you ever get bored?” I once asked. She laughs. “Of course not. It’s a social thing.” Pasta-making for Nonna Agnese, like many Italian women of her generation, is a communal activity – a chance to catch up with old friends, talk about the world (within a 5km radius), catch up on the latest gossip, and complain about aches and pains. And when friends are not at hand, she cracks the matriarchal whip and puts the family to work!

Like Agnese, Sabrina Piazza knows more than a thing or two about pasta. The 30-something chef has been running the kitchen of the family-owned Antica Locanda del Falco for years. Making fresh pasta is the first order of business every morning. “Here in Emilia, fresh egg pasta is expected. It’s the tradition,” she explains. She’s not complaining, merely stating a fact. It is a tradition that has been handed down from generation to generation. Sabrina learned her skills – like most Italian cooks – from her mother and her grandmother. Skilfully she continues to roll, cut, fill and shape ravioli with lightning speed, hardly watching what she is doing, while talking at the same time. The process is intrinsic. “Pasta is fundamental to us. Fundamental to our history and to our roots. It’s something every Italian comes to expect.”

Italy: The Home of Pasta

Some years back, the pasta manufacturing giant Barilla launched an advertising campaign with the catchphrase Dové c’è Barilla, c’è casa (where there’s Barilla, there’s home). Like all good advertising campaigns it bore more than a modicum of truth. The sentimental chord struck by the ad was the notion that pasta and home are somehow synonymous.

The truth is that although you won’t find a packet of Barilla adorning every household store cupboard in the country (after all, Barilla isn’t the only producer), you will find that virtually every person in the country, whatever their generation, whatever their background, has grown up with pasta. A collective memory, pasta is intrinsic to the national psyche. It is the one great unifying force in a country of regional dialects.

When you watch Italians in a restaurant or in their homes eating pasta, you see it eaten with total joy and enthusiasm, somehow belying the fact that it is a daily ritual. Perhaps the explanation is rooted in the history of its rise to prominence. Pasta derives after all from humble origins – a means to feed a starving population. The joy and animation with which Italians today still take to their daily pasta is, perhaps, more than anything else, recognition of how far they have come and an expression of gratitude.