Think of Italy and its most well-known food exports, and a third of them come from one region: Emilia-Romagna. Alexander James finds out why this part of the country is such a gastronomic hot-spot…

Photos by Bologna Welcome (www.bolognawelcome.com) unless otherwise stated

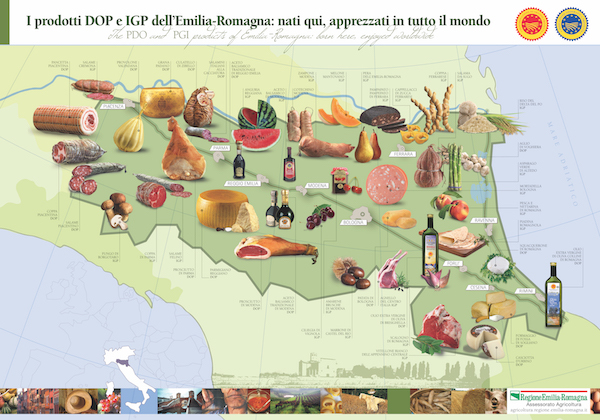

Visit this region between the Adriatic Sea and Tuscany and you’ll find the origins of your supermarket favourites. These offerings read like a deli’s wishlist: Parmesan and Grana Padano cheeses matured to perfection, authentic balsamic vinegars that have taken millennia to perfect, plus joints of ham: Modena prosciutto, Parma, pancetta, salami and mortadella. And that’s before you tuck into a lasagna from its original birthplace, washed down with a native Lambrusco. The area has 42 names of food protected by PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) and more than 200 on the ministerial register, plus 19 museums dedicated to the pleasures of food.

More often this area is overlooked as a travel destination in favour of the classic destinations like Venice, Rome, Tuscany or the lakes, making all that you encounter here truly hidden gems – the kind every visitor wants to discover for themselves. Even better, you can spend a month making a tour through its specially designated ‘Food Valley’ (see map below).

And that’s just the gastronomy. Emilia-Romagna also packs in such feats as being home to Europe’s oldest university, at Bologna, as well as spawning the kind of tech-savvy brains whose later generations founded the region’s supercars: Lamborghini, Maserati and Ferrari.

On the artistic side, its heritage includes the homes of Luciano Pavarotti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giorgio Armani, Federico Fellini and the 14th-century artist Giovanni da Rimini, who might not be as popularly famous as the others but is a kingpin in the world of art history. Some of Giovanni’s art has recently been on rare display at the National Gallery of Art in London.

The question remains: Why, more than other parts of Italy, are the country’s prevalence of flagship names to be found here? The answer lies in history, back when Romans forged the landscape.

On the Via Emilia

One big road threads through the region. It is known as the Via Emilia and it was built by the Romans. It was key to developing the empire’s political and cultural hold. Today it is one of Europe’s best road trips. Think of it as the Roman Route 66. It cuts through Apennine valleys, over bridges, rivers and sweeping vistas, moving from Rimini – Forlì – Bologna – Modena – Reggio Emilia – Parma – Piacenza. You’ll spend one of the most culturally enriching rides of your life on this route.

“Along these roads, every 55 to 60 km there is a town,” says historian David Ceccherini. “This is how far a Roman army could march in one day before setting camp. Today’s towns evolved out of these camps.”

So when the western world’s first university was established in Bologna in 1088, the explosion of creative technical knowledge that occurred here was quickly passed from city to city. Experimental tastes of new students spawned a market for produce to cater to eclectic tastes, distilled into an ever-evolving search for perfection. This culminated in the International School of Italian Cuisine near Parma, founded in 2003.

“For over two thousand years, adventurers and daring spirits have travelled the Via Emilia,” says Andrea Corsini, Minister for Tourism in Emilia-Romagna. “This coming and going of people, goods, ideas and experiences has brought so much excellence to Emilia-Romagna. From the oldest universities to modern biotechnology, the region’s traditions are renewed every day, through the practice of timeless methods and the knowledge of how to do it well.”

One other factor is the region’s obsession with documenting its history, passing on learning to new generations. Bologna’s ancient university library at the Archiginnasio is testimony to this. So too is the classic Anglo-Italian favourite spaghetti bolognese. Many assume it originates from Bologna. But order one of these here and you’ll likely get beaten around the head with a length of salame di Felino for gastro-blasphemy.

Tagliatelle al ragù

There is, however, one similar recipe from Bologna, which is a city signature dish: tagliatelle al ragù. The benchmark copy of this recipe of has been locked away at the Chamber of Commerce since October 17th, 1982, to preserve its authenticity. Among the specifications: the width of the tagliatella must be 12,270th the width of the city’s Asinelli Tower (which is, in fact, 8mm).

This free-flowing of ideas, influencing one town from the last, has been triggered by another factor. Some of the most radical attitudes in Italy are found in this region, pushing the necessary boundaries for staying creative. Bologna is often known as the ‘red city’, not just for the stunning brickwork and terracotta roofs of its buildings, but for the politically left leanings that go against the grain. Its neighbouring town, Modena, was also a key figure in the anti-Nazi resistance during World War II. The city’s square is the only place in Italy to have photos of all those who lost their lives adorned on a memorial to their bravery.

Others might point to the fact Mussolini had his holiday home just 145km west, in Rimini. The country’s Fascist dictator and leader (who started his career as a socialist) led to the popularity of the resort

as a holiday destination.

Breaking boundaries

“Our history is one of breaking boundaries through art, and sometimes through controversy,” says local guide Raffaella Cenni. “From the kind of 14th-century frescoes you can see in our church, which influenced the Renaissance, to Federico Fellini, to our new food revolution of the biological food movement that is gaining ground today.”

The impact on creativity is still felt on an international level. Just like those frescoes, simple by design, but able to flourish on a sophisticated world platform. One chef who has decided to bring it to the world of metropolitan glamour is Marco Torri, head chef at Novikov in Mayfair, London. He introduces some of the Emilia-Romagna region’s delicacies to a series of chef masterclasses this year.

“Emilia-Romagna has given us world-famous luxury sports car brands like Ferrari, Lamborghini and Ferrari, so it’s no surprise that it’s offered us cuisine that resonated with restaurants, hotels, supermarkets and homes around the world,” says Torri. “The region’s fertile landscape provides a climate for the very best charcuterie and fresh pasta, which is mainly down to the quality of its eggs.”

“One favourite of mine is the region’s traditional balsamic vinegar. This is aged for at least 12 years in different wooden barrels and should never be confused with ordinary balsamic vinegar. Just as the region’s Lambrusco should not be confused with the sickly sweet wine of the 1980s,” says Torri.

“The legacy of balsamic vinegar is truly ancient, once used by the Romans in place of sugar and as a medicine in medieval times,” he adds. “This region is one of Italy as a whole. It is blessed to have the sea, mountains, lakes, hills, plains, weather, history and people that shaped the region’s produce and recipes. I wouldn’t swap this culinary heritage for all the Ferraris in the world.”

More information

Emilia-Romagna Tourist Board: www.emiliaromagnaturismo.it

Find out more about the region’s foodie cities here.